Life has a way of intervening in the best laid plans. When the plans are less than best-laid, the intervention can result in massive chaos. My life the past several years has been, you guessed it, massive chaos.

I put on a good front, I think. Most of my online companions would be aghast at what goes on behind (or in front of) the screen. While this post is not intended to elucidate that reality, I'm using it as a justification.

Justification for what?

You'll see.

In the spring of 1999, as I was enjoying my much-delayed return to higher education at Arizona State University, I began collecting the research material for my proposed honors thesis, an examination of the cultural impacts of romance novels. Completion of the thesis was planned for May 2000, so I had plenty of time.

I amassed a considerable library, though much of the material was a bit on the disappointing side. Few of the academic analyses of romance fiction actually included much romance fiction. Oh, there were references to it, of course, but little actual analysis of the texts. "How," I thought, "can you even hope to explore the impact, whether positive or negative, of romance novels if you don't even offer some examples? How can you support your thesis -- pun intended -- if you don't present any evidence?"

So I set out, over the next twelve months, to write my thesis on that foundation.

I had what I thought was a reasonably unusual, if not unique, vantage point from which to write. Not only was I an avid reader of romance, but also a published writer thereof. I had sold seven historical romance novels to four different New York publishers between 1984 and 1996. Not a particularly prolific career, but it certainly put me into the "published" category, rather than just an aspiring scribbler. (Yes, that's a pejorative, to be explained later.)

I had also been a member of Romance Writers of America for well over a decade, had served on the committee for the RWA national conference, founded a local Phoenix chapter of RWA and served as its president. Through that chapter I organized a contest for unpublished romance writers and judge in that contest's first three annual iterations. I also founded a special interest chapter solely for published authors. As president of that latter chapter, I organized three national conferences -- two in New York and one in Los Angeles -- focused on the professional interests of professional writers.

Even after leaving RWA -- and my romance writing career -- in 1998 to return to college after a 25-year hiatus, I continued to read romance fiction. And though I had given up on ever writing more of it, I retained my interest in the genre beyond just a means of entertainment, escape from the daily grind of housework, parenting, and study.

If there was one quote that focused my endeavor, it was this line from Dale Spender's The Writing or the Sex, or why you don't have to read women's writing to know it's no good:

I have long wanted to place a D. H. Lawrence novel between the covers of Harlequin/Mills and Boon, and to test its status when seen in this light. (p. 79)

Because I read Spender in 1994, before I even thought about going back to college, and because I had read Lady Chatterley's Lover decades before that and recognized it as a romance novel, her statement struck deep. Romance novels, far more than Rodney Dangerfield, got no respect. They didn't when she wrote it in 1989. They didn't when John Cawelti gave the entire genre only one-and-a-half pages in his Adventure, Mystery, and Romance in 1976.

I proposed to change that in 2000. Of course, life intervened and my thesis, titled Half Heaven, Half Heartache: Discovering the Transformative Potential in Women's Popular Fiction ended up being much, much shorter than originally planned. It was still more than enough to grant me my honors degree, and also more than enough to surprise the members of my committee when I defended it.

And that's what really surprised me.

Two of the three were professors of English, the third of history. They had known the subject matter of the paper for weeks ahead of time, and one had known for several months. I gave them copies a week or two before the defense, anticipating tough questioning because I knew the topic was at least mildly controversial. But their questions were more founded in curiosity than in an attempt to prompt a serious defense of a serious position. They knew nothing about romance fiction. Nothing.

Well, I take that back. They knew enough to be somewhat befuddled by the idea that all romance novels aren't Harlequins, and they knew enough to ask what, if any, difference there was between romance novels and television soap operas.

(If you rolled your eyes at that, please, pick them up off the floor so you can continue reading.)

But again, that was 2000. I had a serious nibble from a respected publisher on a book-length version of the thesis, but life intervened and I was never able to put it together. I went on to graduate school and got my master's, and shortly after graduating I found myself suddenly widowed and forced to focus on the harsh realities that accompanied that change in status. Even so, that long personal involvement with romance fiction never left me. I continued to read in the genre, though not as extensively as I had before simply because I couldn't afford to buy all the books!

And I kept all my research material. There were those who urged me to "clean house," so to speak, but I resisted.

Then came digital self publishing. I knew nothing about it and discovered it almost by accident. I found it more than a little intriguing.

In 2011 and 2012, I explored the possibilities of re-issuing some of those historical romance novels I'd published in the 1980s and 1990s. I had no budget for hiring someone to do the work for me, so I did everything myself, except the cover art. I blew more money than I could afford on covers for re-issues of four of the seven, with mediocre results. But I was reasonably happy. I was in control, and I found that to be a very heady experience.

My last publisher, Pocket Books, would not revert the rights to me, so neither Moonsilver nor Touchstone were mine to re-issue. After the horrible experience I had with that publisher, the horrible editing, the beyond horrible cover art, the utter lack of promotion, I already disliked them intensely. Their refusal to allow me to republish the books sealed the deal, and when they put trade-paperback editions on Amazon with outrageous prices, I knew they didn't want to sell the books; they just wanted to keep me from doing likewise. I lost what tiny little bit of respect I had for traditional publishing.

I took a little gamble and put a digital edition of Half Heaven, Half Heartache on Amazon, with cover art I did myself. It wasn't an effort to make money so much as it was self validation. How many copies has it sold? I don't know, but I'm sure it's fewer than a dozen. I don't care. It's there.

Around the same time I was putting my thesis on Amazon, I engaged in some online conversations with credentialed academics on the subject of romance fiction and feminism and empowerment, but I felt somewhat dismissed, if that's the right word, because I wasn't in their world. When I questioned the tiny sample of romance fiction used in one academic research project, the researchers told me they didn't have sufficient budget.

Hello? You can pick up used paperback romances at thrift shops and used book stores and church rummage sales! Check them out of the library! (Personally, I think it was just an excuse: they really didn't want lower their academic selves to actually read romance novels.)

I rolled my eyes and picked them up off the floor, then silently wailed that I still didn't have the means, the time, or the academic reputation to pursue the project that had been lurking in the back of my head for over a decade.

Instead, the writing spark touched me again and in 2016 I finished a novel I had begun in 1994. The Looking-Glass Portrait went up as a Kindle edition on Amazon with a cover I made myself using artwork purchased on Etsy. I had no advertising budget, wasn't even on Twitter or Goodreads at the time, but over the next year or so I made more income from that book than from any of the traditionally published books I'd written. In fact, more than from the first five put together!

I not only made more money, but I made it quicker. None of this waiting weeks before signing a contract, waiting months for the advance money, then years for publication, then more years for royalties (if any).

"Why," I wondered, "would anyone still mess around with publishers who pay maybe at best ten percent royalties when I can collect seventy percent from Amazon?"

To my way of thinking, digital self-publishing should have meant a massive revolution to the romance fiction industry. I began thinking about that analysis of mine again.

One thing held me back, and one thing only.

In 2003, Pamela Regis published A Natural History of the Romance Novel. I knew I couldn't compete with a real, credentialed academic. No way. For a long time I couldn't even afford to buy a copy of Regis's book, and I would have been secretly humiliated to read it. Was this imposter syndrome at work? Probably. But then I found an inexpensive used copy of the book and grabbed it, even though I still expected to be humiliated within the first few pages.

You're not good enough, my inner critic warned with a malicious chuckle. They're all professors of this and professors of that, and you're not.

The problem was that as I began to read Regis, I found myself immediately disagreeing with much of what she wrote. Of course that meant my ideas were wrong and hers were right and I needed to just go back to being a failed romance writer no one paid any attention to.

Maybe, just maybe, some of that changed today, all as a result of a serendipitous post on Twitter that led me down a research rabbit hole, where I discovered a few books and a doctoral dissertation.

The books for the most part are outrageously, even obscenely expensive. Over $50 for a Kindle edition? Paperback nearly $60? Hardcover over $200?!

But as I looked at the sample of that $50+ Kindle edition, I recognized something I hadn't thought of before, not when I was writing my little thesis in 2000, not when I was reading Regis in 2016, not when I was reading that dissertation a few hours earlier.

These are all books written by professional academics for professional academics. They're priced out of the reach of readers of romance fiction and probably out of reach for many of the writers of romance fiction.

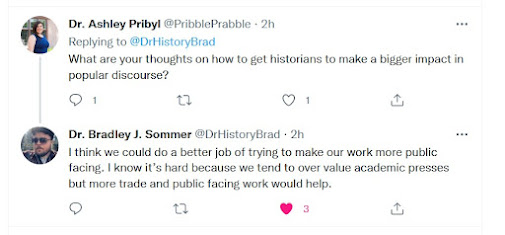

And then there's another academic on Twitter tonight:

"Make our work more public facing." Hmmm.....

How can the public afford a $200 book? How many romance readers can afford it? Or have the academic language to appreciate it? Oh, wait, it's not written for romance readers. Or for romance writers. It's written, published, and priced for other academics. I guess they think if we don't have PhD after our names, we're not worthy of their lofty opinions.

So I bought Laura Vivanco's $0.99 Kindle edition of Faith, Love, Hope and Popular Romance Fiction.

When I wrote Half Heaven, Half Heartache I intended it to be understandable by the average romance reader and romance writer, people just like me. I had been a member of those often overlapping groups for almost all of my life. In the spring of 2000 when I was defending that thesis, I was 51 years old. I had read my first adult historical romance at the age of 12 or 13, maybe younger. I began writing adult historical romance at the same age. I wrote my first complete contemporary romance in 1963 at the age of 15. It's not very good, but I still have most of it.

One of the things that bothered me enormously through the five years I spent at ASU was that academia loved studying popular culture, but generally turned up its collective noses at the producers and consumers thereof. In a course on 20th Century Women Writers, I made the remark that it seemed everything we read in class was depressing and discouraging. "Doesn't anyone believe in happy endings?" I dared to ask. The professor was horrified at the mere suggestion.

No, I did not tell her I wrote romance novels. I think she found out eventually, but by then it didn't matter.

In another instance, I gave one of my professors a copy of one of my books. She knew ahead of time that I wrote romance, but she told me later that as she was reading the book, she kept thinking it was more of a mystery than a romance. There was a murder, after all, and romance novels don't have serious things like murders in them! Well, sorry, but yes they do. Even in 2001 they did.

Then there was that dissertation I found online today. At least that was free! I downloaded the PDF file. It purports to be an ethnographic study of the popular culture of romance focusing on communities and feminism and fandom and all sorts of other things. It's over 200 pages long, and I admit I only read about the first 25 before skipping ahead to the bibliography.

A lot of the sources the author used were very familiar to me; I had used the same references in 2000 writing my thesis. Others were newer, published since then, or on different subjects. What was missing, however, were actual romance novels. She cited only one romance novel.

Listed in the extensive bibliography were Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities; Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice; and Kathleen E. Woodiwiss's The Flame and the Flower. While I personally consider both the Dickens and the Austen works to be legitimately classified as romance novels, I'm seriously disappointed that there's any assumption that romance novels went into some kind of hibernation in 1859 and didn't emerge from their slumber until 1972.

But then I remembered that Kelly Choyke, the PhD candidate who wrote "The Power of Popular Romance Culture: Community, Fandom, and Sexual Politics," was writing for an academic audience who (probably) didn't care about the romance novels that preceded The Flame and the Flower or those that followed, and almost certainly didn't give a rat's behind about the readers or the writers thereof.

That phrase "sexual politics" jumped out at me. Politics, the study of government, of power, of citizens collectively. (My definitions, not formal.) Hoi poloi, as we learned in classical Greek at the University of Illinois in 1966, the people, the common people, the source of "politics." But when it comes to romance fiction, the hoi poloi are just peasants unworthy of notice. Oh, sure, college professors read mysteries for the intellectual challenge, and we all know science fiction is "the literature of ideas." Romance, on the other hand, well, no one who is really educated would be caught dead reading a romance novel.

Now, you and I know perfectly well that's nonsense, but if you try to read Romance Fiction and American Culture: Love as the Practice of Freedom? I think you'll find that it's not addressed to the hoi poloi. We're not worthy. It's over our little heads.

My dear goddess, could they get any more patriarchal, any more hierarchical, any more condescending?

Born in 1948, I came of age in the storied 1960s, when popular culture impacted politics in a very direct way. I wonder now if the true and transformative power of popular culture has been co-opted by the Establishment, who has in turn given us . . . influencers.

The romance novel has undergone changes through its lifetime, and even since 1972 when The Flame and the Flower burst on the scene. But the romance novel as a genre does not exist in a vacuum. As convenient as it may be to isolate it as an object of academic study, it is to the detriment of the readers, the writers, and the overlapping, intersecting, interdependent communities they inhabit.

Isolating romance fiction as an object of academic study, and to a further extent isolating its subgenres from each other, serves to limit and reduce its power. Jayne Ann Krentz, in putting together the essays that comprise 1992's Dangerous Men and Adventurous Women, tried to bridge the gap between academic analysis of the power of romance and popular creation and enjoyment of romance. Krentz came from the romance community, not academia. Her work caught on with the romance fiction community in a way I don't think any other has.

Academia may lament, as Dr. Ashley Prybil did on Twitter, that they aren't having sufficient impact, but I haven't seen much effort on the part of academia to make their work accessible, by which I mean affordable and understandable.

In the thirty years since Dangerous Men and Adventurous Women was published, has there really been anything written from inside the Romancelandia community, by and for the residents of Romancelandia? I don't recall any. I think it's time for something new.